The Basic

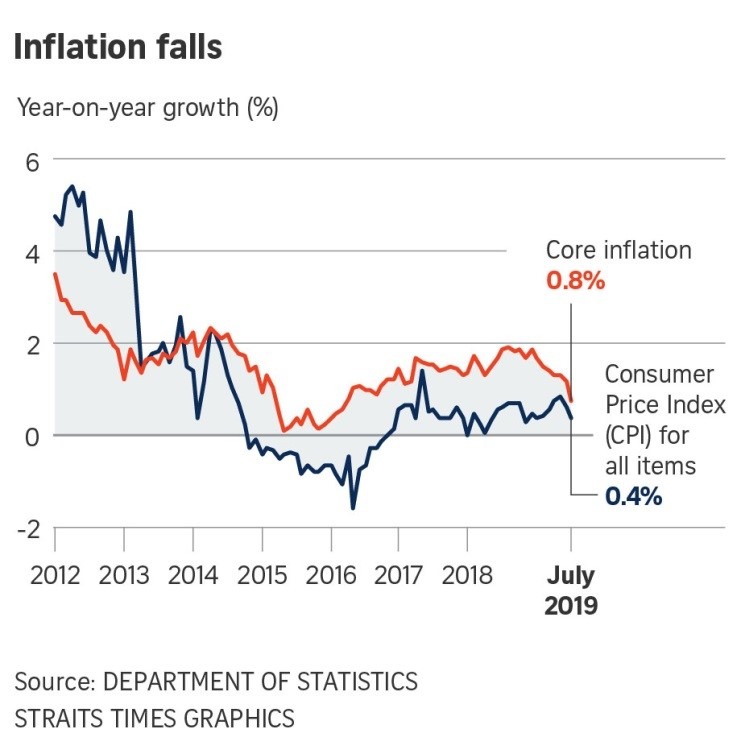

Inflation is defined as an increase in the overall level of prices in the economy. In Singapore, the most common measure of inflation is the annual percentage change in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). CPI measures the cost of a fixed basket of goods and services commonly consumed by resident households, and is measured by the Department of Statistics (DOS) on a monthly basis. Another measure called “Core inflation” is CPI excluding the components of ‘Accommodation’ and ‘Private Road Transport’. It is an additional indicator to track prices that are reflective of core inflation as private road transport and accommodation costs are subject to short-term fluctuations. Core inflation fell to a 3-year low of 0.8% in July 2019. Headline inflation, or CPI, was 0.6% (2017 average), 0.4% (2018 average) and 0.4% (Jul 2019) respectively.

“I don’t believe this. The price of public transport went up by 4.3% last year, and yet the reported official inflation (CPI) was only 0.4%!”

It is not unusual to overhear such complaints, yet did our statisticians really get it wrong? Actually, there is nothing wrong with the numbers. Inflation is a rise in the overall average price of all the items that we buy, and not only one or a few categories of items. The price of each item is weighted by their relative importance in the basket of goods and services.

The pitfalls of excessive inflation

But why is inflation of concern to every one of us? Inflation indicates a decrease in the purchasing power of each dollar, which is why many people aim to “beat inflation” by investing. Excessive rates of inflation, whether too low or too high, are detrimental to long-run economic growth. Inflation that is too high results in the following costs

- formation of asset bubbles, because households and firms become preoccupied with short-term, unproductive investments which are perceived to yield more attractive returns in an inflationary environment, such as property. This could create the illusion of temporary financial well-being while masking fundamental economic problems

- wage-price spiral, which is workers asking for higher wages when they observe inflation in order to maintain their purchasing power, which causes employers to have to charge higher prices to cover the higher wage cost, which leads to workers asking for higher wages again.

- Economic hardship, experienced by individuals whose incomes don’t keep paces with rising prices (retirees)

While high inflation is not desirable, deflation can be harmful as well.

Deflation is a general decline in prices for goods and services, typically associated with a contraction in the supply of money and credit in the economy. British economist John Maynard Keynes cautioned against deflation as he believed it contributed to the downward cycle of economic pessimism during recessions when owners of assets saw their asset prices fall, and so cut back on their willingness to invest. Economist Paul Krugman noted three effects of deflation, namely that people become less willing to spend because they expect falling prices, rising real debt also depresses spending, and workers face wage declines or unemployment as prices fall.

Low and stable inflation is necessary evil

Low and stable inflation (like what we have in Singapore) is preferable to deflation and high inflation. Other countries actively aim to achieve low and stable inflation with their monetary policy, such as the Federal Reserve of the United States. This is because theoretical and empirical arguments by economists have shown that an environment of low and stable inflation is essential for sustainable economic growth. There are many benefits of low inflation:

Firstly, if inflation is stable, firms and consumers are better able to make long-range plans because they know future costs and prices (for firms), and that the purchasing power of their money (for consumers). This increases the efficient allocation of resources.

Secondly, low inflation means lower nominal and real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates. Lower real interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing, encourages firms to invest in order to improve productivity so that they can stay competitive.

Thirdly, prices rise just enough to encourage people to buy sooner rather than later, which stimulates demand just enough for sustainable economic growth. Lower real interest rates also encourage households to buy big ticket items such as houses and cars.

Low inflation is also self-reinforcing. If firms and households are confident that inflation is under long-term control, they do not react as quickly to short-term price pressures by seeking to raise prices and wages. This helps to keep inflation low.

Now we know why countries aim for low and stable inflation, let’s take a look at how Singapore has fared by this benchmark.

Singapore’s inflation experience

If low and stable inflation is an internationally recognised benchmark of monetary policy success, Singapore has had a stellar report card. Since independence in 1965, Singapore has achieved relatively high economic growth and low inflation. Between 1965 and 2016, Singapore’s real GDP growth averaged 7.6% per year. Robust economic growth was not achieved at the expense of high inflation, with CPI-All Items Inflation of 2.7% per annum during this period while MAS Core Inflation averaged 1.4% between 1984 and 2016. This compares with inflation of 22.6% per annum in emerging and developing countries, and 4.5% per annum in advanced economies since 1969.

Nevertheless, as our population ages, more and more households, including most elderly households, are not earning any income from work. Thus, to them, even low inflation is always a problem. The government is mindful of the problems these households face, and has provided significant assistance to older individuals (Pioneer Generation Package, Merdeka Generation Package

While the rest of us non-retirees also receive GSTV-cash vouchers (albeit without the Medisave top-ups), the government central strategy to help us manage increases in costs of living is to grow the economy in a sustainable way and raise skill levels, so as to help wages grow. This is partly the reason behind Singapore’s big productivity drive and Skills Future schemes. How this strategy fares remains to be seen.

However, what is clear is that moderate increase in cost of living due to low and stable inflation is a necessary evil, and we are (counterintuitively) better off because of it.